This article is more than 1 year old

On International Woman's Day we remember Grace Hopper

The Rear Admiral who changed the world of computing

Feature Once again some of the world is celebrating International Woman's Day (IWD), and it's time to reflect on great female role models. Ada Lovelace usually grabs most of the attention but I'd like to use IWD as an excuse to pay a tribute to a personal female hero of computing: US Rear Admiral Grace Hopper.

Amazing Grace was in at the start of the modern computing revolution and dedicated her life to making computers more distributed, easier to use, and more efficient. She invented the first code compiler, was pivotal in the development of COBOL, popularized the term "bug", and was so good at what she did that the US Navy couldn't let her go – recalling her twice to duty before old age did her for good.

That any individual did all this is remarkable, but the fact that she managed to do it as a woman in that era is truly amazing. We live in more enlightened times these days, but Hopper (then Grace Brewster Murray) was born in 1906 and grew up in an age where women were supposed to be seen and not heard.

Hopper did more than most to beat chauvinism in our industry, not by protesting or insisting on special treatment, but by getting out there and doing the job better than anyone else and making men realize they were wrong in their sexism. She became renowned for saying; "If you've got a good idea then go ahead and do it. It's always easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission."

Don't mess with Amazing Grace

Japan's loss, the world's gain

Like Lovelace, Hopper was blessed with parents who were insistent that she receive as good an education as her brother, and she was accepted at Vassar at the tender age of 17 to study mathematics and physics. She joined the faculty there, but carried on studying at Yale to earn her MA in 1930 and a PhD in 1934.

But it was the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that catapulted Hopper into the front line of computing. Initially rejected by the Navy for being too old (34) and skinny, she persisted and was accepted into the Naval Reserve in 1943. She went to the Midshipman's School for Women and graduated at the top of her class.

She was immediately posted to the Bureau of Ordnance Computation at Harvard University and was one of the first people to program the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, better known as the Mark I computer. She wrote the instruction book on how to use the system, and never stopped working with computers after this introduction.

In 1945, the war – and Hopper's 15-year marriage – ended, and she applied to join the Navy proper, but was again rebuffed on age grounds. She turned down the offer of a full professorship at Vassar to stay in the Naval Reserve and remain at Harvard, working with the Mark I, II, and III computers.

Bugs and COBOL

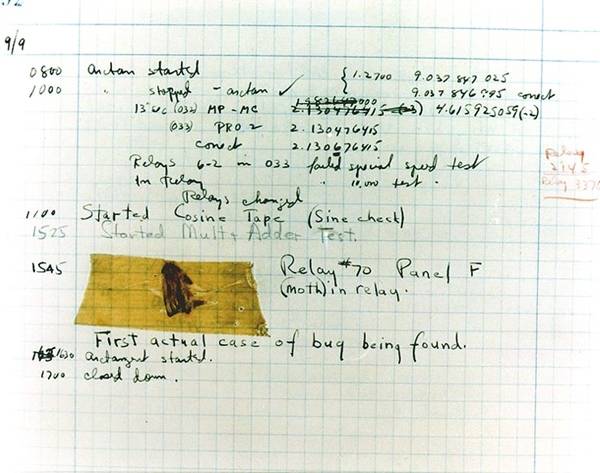

It was while working on the Mark II that on September 9, 1947, Hopper began popularizing the term "bug" to describe a computer error. Back then the bug in question was an actual moth, which had fallen into one of the computer's mechanical relays and jammed it. Hopper never claimed she invented the term, but she did popularize it and the term "debugging" to describe cleaning-up software.

Back when bugs were bugs

In 1949, Hopper transferred to work on the Binary Automatic Computer (BINAC) and the UNIVersal Automatic Computer I (UNIVAC I), a commercial computer designed by Eckert-Mauchley Computer Corporation, which later became Unisys. There she worked with with other important female programmers Betty Holburton, Kay McNulty, Marlyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Betty Jean Jennings, and Fran Bilas.

Up until this point Hopper had worked on punch card programming, but with the move she now began to program in C-10, which required her to learn octal, the base-8 number system. But it wasn't a great solution and she wanted to simplify the programming system.

To this end, in 1952 she invented the first compiler, A-0, which translated mathematical symbols into machine code, and updated the system with A-1 and A-2 the following year. "Nobody believed that," she said. "I had a running compiler and nobody would touch it. They told me computers could only do arithmetic; they could not do programs."

At the same time she was becoming concerned that computer languages were needlessly complex and began to push for standardization. In 1954 her department introduced the FLOW-MATIC programming language, which used limited English phrases. It was this that led her to play a pivotal role in developing the COmmon Business-Oriented Language (COBOL) in 1959.

Showing the boys how it's done

COBOL was one of the most successful computer languages and is still in use today. Research by Datamonitor found that in 2008 there were between 1.5 and 2 million developers still working with the 50-year-old programming language, adding five billion lines of code to the 200 billion already running on live systems.

Navy plays push-me, pull-you

In 1966 Hopper was retired from the Naval Reserve on the grounds of age, but the military found they couldn't live without her and she was reactivated less than a year later – the first woman to be so engaged. Five years later, at the age of 65, she was let go again and then promptly rehired the following year.

She spent much of her time traveling the country lecturing on computing and programming, inspiring the next generation of technologists to try new things. She said that the work she did in teaching was the most satisfying or her career.

The editor of El Reg's Vulture Annex here in San Francisco was fortunate to meet Hopper during a talk at the city's Exploratorium science museum, and received one of her trademark nanoseconds. This is an 11.8-inch (30cm) piece of wire representing the total distance light can travel in a nanosecond, which she used to great effect to encourage tighter coding, usually while puffing on an unfiltered cigarette.

Retirement

In 1986 she was involuntarily retired from the Naval Reserve (she was then its oldest member) after being promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral, the first woman to achieve such a high rank. She was also presented with the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, the Navy's highest non-combat medal.

'Thanks for your service. Now push off.'

It was not her only award. In 1969 she was won the first "computer sciences man [sic] of the year" award from the Data Processing Management Association, and was the first woman to be made a Distinguished Fellow of the British Computer Society in 1973.

"I've received many honors and I'm grateful for them; but I've already received the highest award I'll ever receive, and that has been the privilege and honor of serving very proudly in the United States Navy," she said in an interview.

The Navy loved her back, and in 1995 she became only the second woman to have a fighting ship named after her. The guided missile destroyer USS Hopper is still on active duty and the ship's coat of arms contains her motto "Aude et Effice" – "Dare and Do".

Hopper carried on teaching, this time as an ambassador for DEC. She still wore her naval uniform to lectures and provided continuing inspiration, particularly to women. Female staff at Microsoft formed a group calling itself Hoppers, and set up a scholarship in her name.

Hopper always said she wanted to see the new century roll over but sadly it was not to be. She passed away on New Year's Day 1996 and was buried with full Naval honors at Arlington National Cemetery. ®

Bootnote

Judging from Twitter and Facebook feeds, a lot of people – men, presumably – seem to be bemoaning IWD as yet another example of that lazy phrase "political correctness gone mad". "Where's International Men's Day?" (IMD) is their clarion call.

As it turns out there is such a day – you can celebrate it on November 19, and it's even endorsed by the United Nations. IMD was started in the West Indian nation of Trinidad by Dr. Jerome Teelucksingh as a day to focus on men's health issues, gender relations, and positive male role models. The date is his dad's birthday.

Some would argue that every day is IMD, but that's a facile argument. Every day is someone's IMD, and it's usually a man holding the reins of power – but not exclusively. On the other hand, the fact that there's a need for an IWD does indicate that there's still a problem to be solved.

Maybe in a few years IWD will be seen as a cute relic of an older, less-enlightened time when sexism was an issue. I hope that day comes soon.